Flags of the Mahdiyya

Item

Title

Flags of the Mahdiyya

Creator

Subject

Mahdi, Sudan, banners

Description

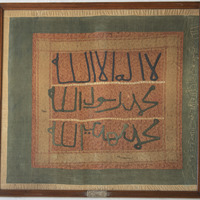

The use of banners by followers of the Mahdī and his successor, the Khalīfa ʿAbdullāhi, was an inheritance from Sudan’s Sufi tradition.

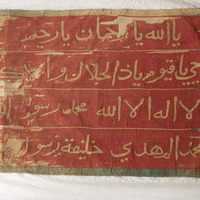

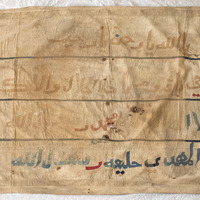

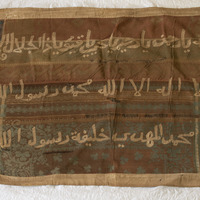

A flag was raised at the centre of the prayer circle when a community gathered for collective devotions; when the group’s sheikh travelled, a banner was carried ahead of him by one of his adherents. In their traditional form, Sufi banners featured the Muslim shahāda – “There is no God but Allah; Muḥammad is Allah’s Messenger” – and the name of the sect’s founder, an individual usually regarded as a saint.

After the declaration by Muḥammad Aḥmad on 29 June 1881 that he was al-Mahdī al-Muntaẓar (the Expected Rightly-guided One), the use of flags also acquired a military dimension. When a government army detachment was sent from Khartoum to detain him and bring him to the capital for questioning, he adapted the traditional flags by adding a quotation from the Koran – Yā allah yā ḥayy yā qayūm yā ḍhi’l-jalāl wa’l-ikrām [O Allah! O Ever-living, O Everlasting, O Lord of Majesty and Generosity] – and the highly charged claim “Muḥammad al-Mahdī khalifat rasūl Allah” [Muḥammad al-Mahdī is the successor of Allah’s messenger (i.e. the Prophet Muḥammad)].

Flags were observed in every military encounter as the Mahdī’s forces achieved a succession of remarkable victories against better-armed forces despatched by the Khartoum administration. At one battle in April 1883, a senior British officer attached to the government army observed the enemy’s flags, “inscribed with the Mahdi’s own rendering of the Koran”, and was reminded of a verse from Paradise Lost in which Milton wrote that “Banners rise into the air / With orient colours waving”.

As the Mahdī’s jihad progressed, banners became specifically colour coded, allowing soldiers of the three main divisions – the Black, Green and Red Banners (rāyāt) – to marshal effectively on the battlefield, alongside the bespoke flags of prominent commanders such as ʿUthmān Abū-Bakr Diqna and ʿUthmān Azraq. Manufacturing facilities, too, became more sophisticated as the anṣār multiplied and were deployed on several fronts. Women were likely to have been involved in that process, selecting the materials, dying indigenous cottons and stitching on the various manifesto formulae. And, just as jibba patches were increasingly tailored symmetrically, so too did most anṣār flags become standardised in layout and formulae of adherence.

By the Battle of Omdurman on 2 September 1898, the largest anṣār contingent – 28,273 infantry and 2,922 cavalry loyal to the Khalīfa ʿAbdullāhi’s son, ʿUthmān Sheikh al-Dīn – had no formally colour-coded banner. The Black Flag division under the Khalīfa’s half-brother, Yaʿqūb Muḥammad, boasted 14,128 infantry and 1,588 cavalry. The Green Flag division was far smaller, with only 5,398 men and 794 horses – while the Red Flag division, its commander disgraced after speaking out against the Khalīfa’s rule, had a pitiful 84 followers and just one horse.

As the battle progressed – ultimately claiming as many as 10,000 Sudanese lives – the largest flag of them all attracted sustained and accurate British gunfire, making its protection a deadly duty. Holes were shot in the black fabric and, as one man fell, another would rally to it. By the time the British reached the banner, the bodies of at least one hundred dead men and 200 more wounded were piled around its timber flagpole.

After the declaration by Muḥammad Aḥmad on 29 June 1881 that he was al-Mahdī al-Muntaẓar (the Expected Rightly-guided One), the use of flags also acquired a military dimension. When a government army detachment was sent from Khartoum to detain him and bring him to the capital for questioning, he adapted the traditional flags by adding a quotation from the Koran – Yā allah yā ḥayy yā qayūm yā ḍhi’l-jalāl wa’l-ikrām [O Allah! O Ever-living, O Everlasting, O Lord of Majesty and Generosity] – and the highly charged claim “Muḥammad al-Mahdī khalifat rasūl Allah” [Muḥammad al-Mahdī is the successor of Allah’s messenger (i.e. the Prophet Muḥammad)].

Flags were observed in every military encounter as the Mahdī’s forces achieved a succession of remarkable victories against better-armed forces despatched by the Khartoum administration. At one battle in April 1883, a senior British officer attached to the government army observed the enemy’s flags, “inscribed with the Mahdi’s own rendering of the Koran”, and was reminded of a verse from Paradise Lost in which Milton wrote that “Banners rise into the air / With orient colours waving”.

As the Mahdī’s jihad progressed, banners became specifically colour coded, allowing soldiers of the three main divisions – the Black, Green and Red Banners (rāyāt) – to marshal effectively on the battlefield, alongside the bespoke flags of prominent commanders such as ʿUthmān Abū-Bakr Diqna and ʿUthmān Azraq. Manufacturing facilities, too, became more sophisticated as the anṣār multiplied and were deployed on several fronts. Women were likely to have been involved in that process, selecting the materials, dying indigenous cottons and stitching on the various manifesto formulae. And, just as jibba patches were increasingly tailored symmetrically, so too did most anṣār flags become standardised in layout and formulae of adherence.

By the Battle of Omdurman on 2 September 1898, the largest anṣār contingent – 28,273 infantry and 2,922 cavalry loyal to the Khalīfa ʿAbdullāhi’s son, ʿUthmān Sheikh al-Dīn – had no formally colour-coded banner. The Black Flag division under the Khalīfa’s half-brother, Yaʿqūb Muḥammad, boasted 14,128 infantry and 1,588 cavalry. The Green Flag division was far smaller, with only 5,398 men and 794 horses – while the Red Flag division, its commander disgraced after speaking out against the Khalīfa’s rule, had a pitiful 84 followers and just one horse.

As the battle progressed – ultimately claiming as many as 10,000 Sudanese lives – the largest flag of them all attracted sustained and accurate British gunfire, making its protection a deadly duty. Holes were shot in the black fabric and, as one man fell, another would rally to it. By the time the British reached the banner, the bodies of at least one hundred dead men and 200 more wounded were piled around its timber flagpole.

Publisher

Making African Connections

Relation

Rights

© Making African Connections

Linked resources

Filter by property

| Title | Alternate label | Class |

|---|---|---|

Fergus Nicoll Fergus Nicoll |

Text | |

Large silk banner, possibly carried by Anṣār (الأنصار) Large silk banner, possibly carried by Anṣār (الأنصار) |

Physical Object | |

Banner carried by Anṣār (الأنصار) Banner carried by Anṣār (الأنصار) |

Physical Object | |

Anṣār (الأنصار) Banner Anṣār (الأنصار) Banner |

Physical Object | |

Anṣār (الأنصار) banner Anṣār (الأنصار) banner |

Physical Object | |

Anṣār (الأنصار) Banner Anṣār (الأنصار) Banner |

Physical Object | |

Interview with Imam Ahmad al-Mahdi, grandson of the Mahdi Interview with Imam Ahmad al-Mahdi, grandson of the Mahdi |

Event | |

Anṣār (الأنصار) Banner Anṣār (الأنصار) Banner |

Physical Object | |

Anṣār (الأنصار) banner Anṣār (الأنصار) banner |

Physical Object | |

Anṣār banner Anṣār banner |

Physical Object | |

| 'The Origins, Development and Use of Banners During the Mahdia', | Article |